It’s been a wild year for cinematic representations of LGBTQIA on film. We got some actual screen time in the biggest film of the year (Avengers: Endgame), in a self-contained scene that could easily be snipped in China, Russia, India, and Hungary despite containing no gay content other than seeming relatably sad. But we also were recognized as the safety net for beloved divas (Judy) and acknowledged, in an unspoken act of atonement for ‘80s ignorance, as a vital and necessary part of the larger communities (Dolemite is my Name).

We’ve had LGBT directors make films for straight audiences and get over (the delightfully inventive Happy Death Day 2 U from Christopher Landon and How To Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World from bear icon Dean DeBlois). As usual, the world of documentary and nonfiction film was presenting complex and interesting LGBT lives as they were lived (Born To Be, Gay Chorus Deep South, Scream, Queen: My Nightmare on Elm Street, Hail Satan?). We’ve even had ostensibly heterosexual filmmakers do their homework and come up with realistic and affectionate queer characters (Booksmart, Rocketman, Charlie’s Angels, Giant Little Ones).

There’s a special archetype, and it pops up in all sorts of films and other media, but it warms my heart, and that’s the “Anything-That-Moves” bisexual character. Sometimes it’s a caricature of hypersexuality, but lately it feels like art is doing right by our siblings with equal opportunity libido (Velvet Buzzsaw, Luz, Bliss). And there have been even more leaps made in pansexual representation.

For the longest time used as a shortcut to represent bourgeois decadence, contemporary film has been making taking the Auntie Mame approach and serving the poor starving world a buffet of all sorts of possibilities (the Brazilian Mad Max/Brigadoon blend Bacurau, the Portuguese trans* soccer beefcake fantasia Diamantino, and Liberté, the Catalan film that exists to prove the adage from David Cronenberg’s Shivers that “all flesh is erotic flesh”).

2019 was a really good year for ostensibly straight filmmakers who make defiantly, weirdly queer films. If you saw The Lighthouse or The Art Of Self-Defense, with their just-this-side-of BDSM power dynamics and sexualized atmosphere, you couldn’t be blamed for thinking they were actually gay films. But nope.

Synonyms, an electrifying French-Israeli coproduction, had more explicit gay content than any of the actual gay films that played in theatres worldwide this year. And what of a visceral masterpiece like Daniel Isn’t Real, where doubt is seen as heterosexist and the act of artistic self-confidence is charged with so much homoerotic energy that one’s id can’t even keep its clothes on?

There’re also those films that have nothing explicitly same-sex (or any sex) going on, and yet cannot be anything but capital-G ‘Gay.’ Think Pee-Wee’s Big Adventure, and you get the idea, because that’s what Maleficent 2 (Angelina Jolie with horns and wings and Michelle Pfeiffer in a skulking dress) and In Fabric (a gorgeous cursed dress that brings decadent highs and skull-crushing, life-derailing lows with it) are.

It’s been an amazing year for queer directors making queer films. Pedro Almodovar’s triumphant return with Pain and Glory, the Kenyan lesbian film Rafiki, Yann Gonzalez’ affectionate tribute to ‘70s gay porn and Italian slashers Knife + Heart, the aforementioned documentary Scream, Queen: My Nightmare on Elm Street, and the (surprise) lesbian shocker The Perfection all told fascinating stories about the lives of LGBTQIA people without holding back.

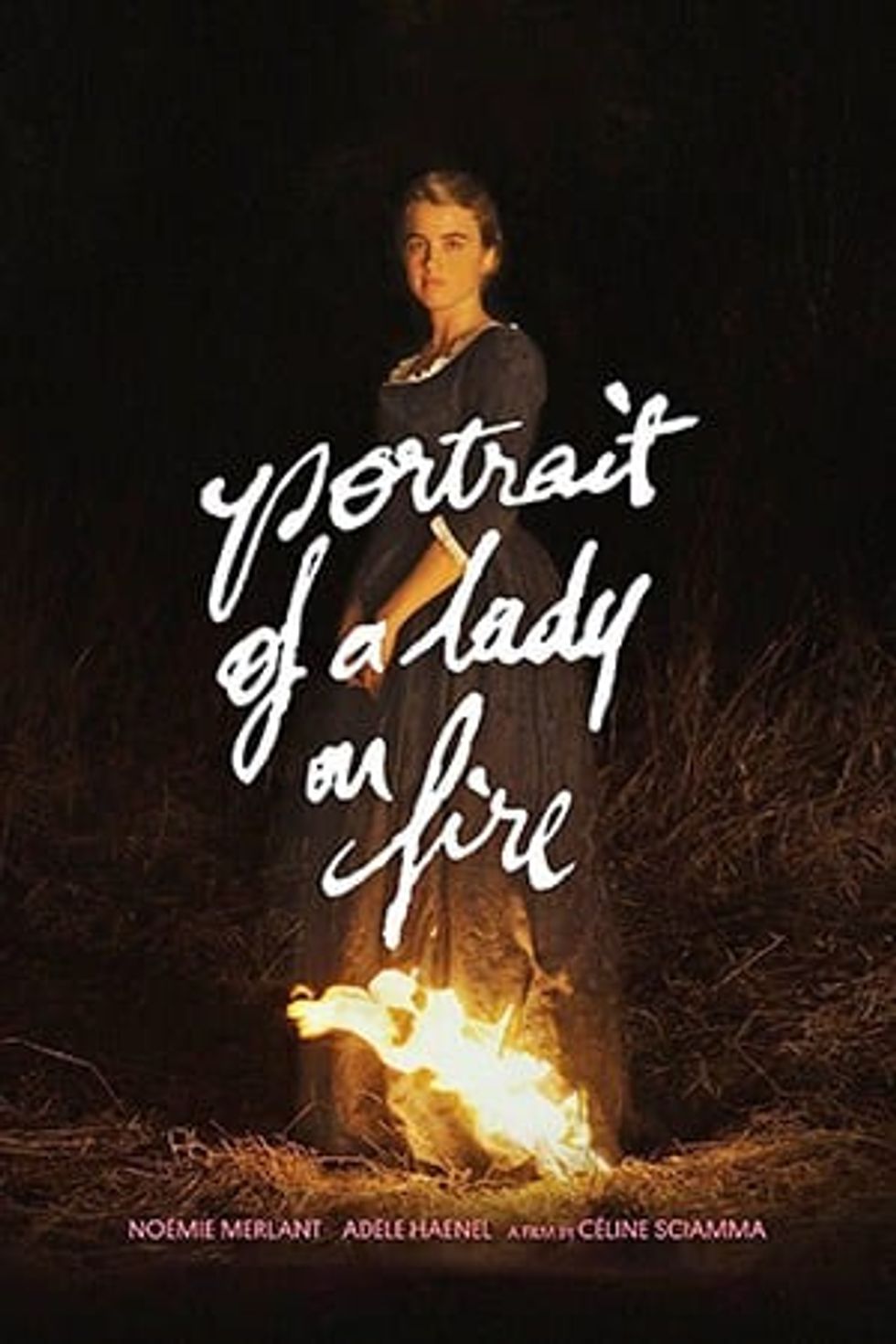

The best LGBT film of 2019, though, is a French drama called Portrait of a Lady on Fire. It’s getting a nationwide release in February (for Valentine’s Day!) from distributor Neon, and it’s magnificent. Lesbian director Celine Sciamma (Girlhood, Tomboy) tells a powerful, meaningful story about how queer desire is the foundation of the vast majority of meaningful art and also how the threat of erasure of our stories is an ongoing menace.

Which is why the film that sticks in my mind as far as queer stories go is It: Chapter Two. This is a film about buried trauma that begins with a graphic gaybashing by one’s own neighbors and ends with the reveal that the closet has done as much damage to a bright spirit as did an extradimensional arachnoid murderclown. We take our representational victories where we can, but we’ve got to have each other’s back- because you don’t have to look very far or very hard to see the creeping terror on the horizon.