By Liz Massey, October 2016 Issue.

Painter Lorraine Inzalaco, who has called Tucson home for the past 20 years, doesn’t shy away from a forthright explanation of why nude females have formed her primary subject matter over the course of her career.

“Painting lesbian imagery is about females together,” she said. “And it goes against the patriarchal art world rules that have stated it was not OK for any female to paint nudes. Throughout history, females were restricted to flowers, still-life, landscapes and making crafts ... I was aware that this was not acceptable subject matter for female artists, so I, and other female artists since the 1950s, have attempted to challenge this oppressive standard.”

After receiving a fairly traditional arts education at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, the University of Cincinnati and Queens College in New York, Inzalaco has spent much of her working years as an artist creating intimate scenes between female figures. These paintings reflect what she refers to as “the lesbian gaze,” an artistic viewpoint that emphasizes creating art that highlights women as subject, and is created primarily for other women to enjoy.

“Our culture has been pressured to see females through male eyes,” she said. “Feminists and lesbians began to … see themselves through the eyes of ‘self’ and other females, and ask ‘who are we as females, as queers and as other identities?’”

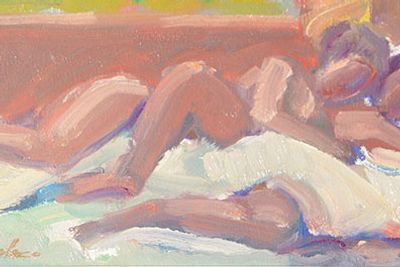

Inzalaco has answered that question through her paintings, which feature an assortment of women, nude and clothed, solo figures and couples, who are living their lives – lounging, entwined in bed together, reading, looking intimately at each other from under brimmed hats. Many of them exude what she calls a “moment of mutual invitation,” that might be subtle to outsiders, but is irrefutable and unmistakable for those in the know.

“I’ve made choices, as an out lesbian, to include romantic, although not always sexual, content,” she said. “The touch of one figure toward another – that moment of mutual invitation – it’s not about the outside world, but about the people involved in it.”

A Love Affair with Art

Inzalaco, who grew up in suburban New Jersey, fell in love with making visual creations at an early age. Her kindergarten teacher set the stage for her future explorations, she said.

“Our teacher would have us lie on the floor, and she would set out a huge sheet of paper for each one of us, and have us get out our eight-crayon Crayola box and draw while she played classical music, and repeatedly told us to ‘draw what you feel,’” Inzalaco recalled. “I was thrilled to be drawing and mesmerized by the entire proces.”

As a child and young adult, Inzalaco had other teachers who encouraged her art, although her family discouraged anything that did not lead to the path of heterosexual marriage and motherhood.

Already firmly established in her dream to become an artist by the time she was in high school, she met her first lesbian partner (whom she was with for two decades) at age 17, and after graduation, the two of them “eloped” to Ohio, where Inzalaco studied at the Art Academy of Cincinnati. Her partner appeared in many of Inzalaco’s paintings and sketches during those years.

“She was beautiful – my muse,” Inzalaco said, “She would pose for me. She’d read and converse with me, and I would paint.”

Although much of her training in college focused on developing her technique, Inzalaco was already drawing on her own life as a woman-loving woman for subject matter. And that eventually led to trouble: during her Master of Fine Art degree program at Queens College, she was placed on probation for her choice of painting scenes from her life, which rarely included male subjects.

“They told me that ‘your painting world is male exclusive,’” she recalled. “They were punishing me for painting the beautiful, authentic life I was living.”

Rather than withdraw or change her visual content, Inzalaco fought back.

“I appealed to the one woman on the probation committee,” she said. “I told her, ‘I’m not leaving, and I want to be graded on my skill and not the subjects of my work.’ I painted for eight months, exhibited a show of 37 works of ‘out’ lesbian love in the graduate gallery, and was awarded my MFA degree based on my skill alone.”

The Struggle To Sell

While Inzalaco had successfully gained her credentials in the professional art world, finding a paying audience for her work remained a struggle during her career.

“There are no galleries in the world that focus only on lesbian work,” she asserted. “I’ve found it difficult to show anywhere, including Phoenix.”

Although finding the right venue for her lesbian artwork – which she refers to “sweet and kissy” – has been difficult, Inzalaco has persevered. She spent many years supporting her art by working full-time as a freelance department-store display designer and as a stylist for professional photographers. She was active with the now-defunct Lesbian Visual Artists, an international association that sought to improve artists’ chances of exhibiting frankly female-oriented subject matter, and she partnered with friendly venues to display her work. She also experimented with selling signed prints of her original paintings, as well as producing small-scale versions of her work on buttons, magnets and greeting cards to increase the reach of her art.

“I’ve come to value the smaller paintings and other ways to present it,” she said. “I love that they are much more economically accessible for people to own.”

Finding Community In The Old Pueblo

“I like that Tucson has a lot of people from all of the bigger cities, who want life to be simple, but also up to date and progressive, too,” she said.

Inzalaco opened a studio and a lesbian art gallery in Tucson for a while, and has been able to exhibit at venues such as WomanKraft Art Center (womankraft.org), which hosted a well-attended solo show of her work in 1997.

Zoe Rhyne, director of exhibits for WomenKraft, echoed Inzalaco’s sentiments that the city is a special place for artists.

“Tucson has a wonderful artistic and cultural soul,” Rhyne said. “There are lots of galleries and exhibit openings, and people who live here like that there is a lot of art available.”

Inzalaco has continued to exhibit at WomanKraft, most recently in a group landscape show over the summer, as well as in other venues. Rhyne noted that despite Inzalaco having found markets more receptive to her work, her experiences were an example of how hard it continues to be for women artists to succeed professionally.

“WomanKraft was founded by eight artists who were tired of being told there was no space for them to show their work because they were women,” she said. “That was in 1974, and we are still incredibly underrepresented in the marketplace.”

Leaving Her Mark

Throughout the past 20 years, Inzalaco said she has worked at detaching her ego from her art making.

“With a bit less ego involvement, I can say that I’m good at art – not great,” she asserted. “If I had put the energy I put into art into being a softball player, I would have been a pretty good softball player. This has helped me release my ego from artistic demands and enjoy the activity.”

Inzalaco’s art continues to gain new fans and provide a glimpse into lesbian lives. Rhyne said she loved Inzalaco’s ability to capture an entire story in one scene and her “raw and honest” approach to her subject matter.

“[Her art] is who she is, and she brings a special energy to everything – even when dropping off her paintings to be hung in a gallery,” Rhyne said. “She never misses a gallery opening … she is making her work because it is important to her, not just to have something to put on the wall.”

Another key to Inzalaco’s current art making is her passion for blazing a visual trail for other artists to be encouraged by – one that wasn’t available to her growing up.

“There are so many blanks in the art history of females. A lot of things just didn’t get recorded,” Inzalaco asserted. “I keep doing what I’m doing to fill in some of those blanks, so that a young queer or questioning female will be able find images that possibly reflect who she is and who she could become, in a healthy way.”

For more information on Lorraine Inzalaco and her artwork, visit inzalaco-lesbianart.com/main.html.