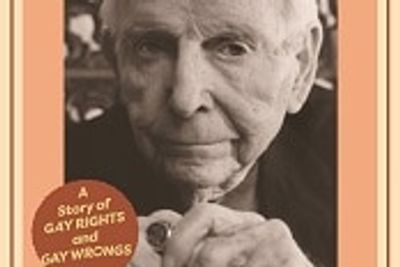

Gay Rights pioneer Morris Kight gets his story told in Mary Ann Cherry’s new book

By Ashley Naftule

“Gay or straight, shy or shining, European or Asian or African, smart or dim, funny or dull, loyal or traitor — there will never be another person quite like Morris Kight.” As closing statements go, Mary Ann Cherry’s epitaph for her subject on the final page of Morris Kight: Humanist, Liberationist, Fantabulist does him justice. Kight, an ardent peace activist, labor organizer, and gay rights pioneer, was truly an American original.

In her new book, Cherry has taken on the task of condensing a life full of political activism, familial turmoil, and controversy into a single volume.

Cherry, who knew Kight while he was alive and established her researcher bona fides as the archivist who maintains the historical records for the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, traces the rise and fall of the “Moses of gay liberation” over his 83 years. From his theatrical background in New Mexico to his work as an activist (for gay rights, labor, the environment, and peace), Cherry paints a fascinating picture of Morris' efforts to put his sex-positive, leftist principles into action.

She also doesn’t flinch from looking into the darker, sadder corners of Kight’s life. She gives a close look at his closeted married life and how his coming out affected his wife and children. She also examines Kight’s failings: how his sex-positive attitude made him reluctant to speak out about sex’s connection to the AIDS epidemic, and how his marching alongside NAMBLA at Pride parades and being a guest speaker at one of their events forever tarnished him in the eyes of many of his peers. To Kight’s credit, he was never accused of being a chickenhawk or being inappropriate with children in any way, and, in the book, Cherry does layout Kight’s (very, very flawed) reasoning for why he didn’t outright condemn the pedophilic organization.

Speaking to Cherry over the phone about her book, we asked her about her experiences with the Kight family, how long it took her to craft this tome, and why this story about gay rights spends so much time talking about the labor movement.

Echo: While I was reading your book, I was really struck by how dense and comprehensive it was. How many years did it take you to write it?

Mary Ann Cherry: I started it shortly after he passed away in 2003—he gave me his blessing. What Morris didn't expect was that I would go to Texas to meet with his former wife. He certainly didn't expect that I'd be talking to his older daughter. The first time that I went to New Mexico and searched around in Albuquerque, I realized the story was going to be bigger than I originally intended. And because Morris was a bit of a controversial figure here locally, I wanted to give it its due diligence. So I was working on it off and on since 2003. My mom passed away during that time, so I took two years off the book. It was never a full-time job, but I just kept going steady at it.

How did his family feel about you writing a book on Morris? How are they grappling with his legacy?

His youngest daughter, Carol, was very supportive right from the get-go; she was able to put me in touch with her mother — his former wife, Stanlibeth. She was willing to talk with me except that she suffered a stroke shortly after the first time that I went. So I had to go back three times. But she was on board: she wanted the story to be told.

One thing I realized is that there’s a lot more victims than the one person living in the closet. There’s a lot of heterosexual lives that are left in a shambles as a result of one person living in the closet. And they were examples of it now. His oldest daughter was estranged from Morris, so she wasn't on board at first. By the time I went back to Texas for the third time to speak with her mother, she was very cooperative. And in the 11th hour she came up with some beautiful photographs of herself as a baby with Morris that no one has ever seen. She finally realized that she was a casualty of all this, but she also found value in the story being told.

You mentioned earlier that Morris is still a controversial figure locally. Is that related to the “Unpopular Choices” section in your book where it talked about Morris’s brief association with NAMBLA and his reluctance to speak out about AIDS?

It was all of the above and a little bit more. He had such a huge ego ... and as I say in the book, it was going to take a big ego to do what he did. Many egos, actually, to undo the many wrongs that were done to homosexuals. Morris, his ego, and the way he entered a room and took it over — he almost forced people to compete on his level and created a climate of competition, good competition. I want to say it was a friendly competition, but sometimes some people can't see that for what it is and they just go in for the negative.

Later in his life — like the last 10, 15 years — he was very worried about his legacy. He started to make claims on the gay rights movement, claims to certain things that stepped on other people's toes. He ended up slighting some good people along the way. And then by the time the NAMBLA thing came around that probably just sealed it for some people.

You do present a very balanced picture of Morris.I was wondering: as you're writing it, knowing him as well as you did, knowing him when he was still alive, was it hard for you to maintain your objectivity while kind of researching his life and trying to create this portrait of the man?

Definitely. I was blessed with some very good advice early on. A gentleman who sort of mentored me for the first few years — his name is Stuart Timmons, he wrote the Harry Hay biography — he gave me some really wise advice. He told me to “take your time because everything you do in this book is going to take three times longer than you anticipate it's going to take.” He was not kidding.

He also told me, and this was so important: “Give yourself permission to change your mind. Change your mind a couple of times and then change it back.” As I was doing the research and writing it, there were times where I had to step back and give myself permission to not like Morris, to not like some of the things he had. And then I was able to come around to a more open acceptance of it all.

You spend a lot of time in the book laying out how deeply interconnected the struggle for gay liberation was with the labor movement. It’s fascinating to see that close relationship between them because nowadays, in modern American politics, it seems like they’ve become two separate spheres.

There’s just no way that an effective gay rights movement could have been born from a law abiding right-wing populace. It had to come out from the left. It had to come from the hippies, really, and that will always be connected with the antiwar movement and the labor movement. Morris was just a perfect example of all of that. He was a living, walking example of all of that.

Now, the gay movement has changed. Most of the households are double income, no children. So that gives them an advantage over a lot of other households. So yes, it has changed. And I don't think the labor movement, the intersectionality of the early gay movement, I don't believe that exists as strongly as it did back then.

It's interesting to think about how somebody as radical as Morris could help create the conditions, the social acceptance that allowed somebody as radically opposite to him as Pete Buttigieg to be taken seriously as a Presidential contender.

It’s fascinating, isn’t it? I was so happy to see Buttigieg up there. He wouldn’t be my first choice: too moderate! He'd be way too moderate for Morris. Mary Ann Cherry’s Morris Kight is available via Process Media.