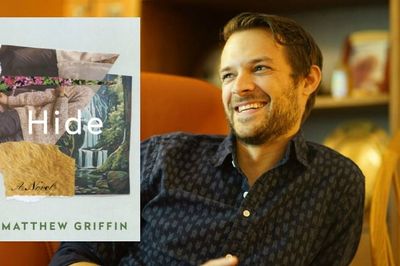

When Matthew Griffin began his interview by admitting he was calling from “the parking lot outside of a diner and a Staples” in Pigeon Forge, it’s obvious his humility will govern the conversation. Griffin, 31, seems a bit surprised at the attention he’s beginning to receive, which is funny because his upcoming book Hide (Bloomsbury) is sure to spark conversation.

“Thank you for wanting to talk to me,” he joked. He recalled telling his University of Louisiana at Lafayette writing students that, “If you hate [my book], you can disregard everything I told you.”

Griffin’s debut novel follows the story of two elderly men living together as partners in a rural North Carolina milltown as they approach the end of their lives. Knowing their relationship would not be tolerated after they first met and fell in love in the 1950s, the couple build a home in seclusion and cut off most ties to the outside world for decades.

But the novel carries less of a political message regarding queer love than might be expected, and through conversation with Griffin it becomes obvious that the parts of the book he finds most meaningful are those about end-of-life reflection. “I’m interested in time and the way people and relationships change over time,” he said.

After a “horrible breakdown” upon realizing his first attempt at a novel “wasn’t any good,” Griffin claims to have “wandered about the house like a ghost for a few days” until the idea for *Hide* came over him rather suddenly. Sorting through passages from his old work, he came to love the ones centered around an older couple best.

The characters in Hide—one a taxidermist and the other a World War II vet—were based heavily on Griffin’s grandparents, a sort of fusion of both sets. “As a gay person myself, [I wondered] what it would have been like to maintain a relationship the way they maintained a relationship,” he said, “with all the added difficulties of having to be closeted at that time and then also having to take care of that person at the end of his life.”

Griffin has found the kind of love worth maintaining with his husband Raymie Wolfe, a musician from East Tennessee. The two met about a decade ago at a bookstore in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, where Wolfe worked while both were finishing up their degrees. “When Matty arrived at Borders, I remember he was wearing like this seersucker jacket kind of a thing, and it really was a little bit like slow motion,” said Wolfe of their first encounter.

He says Griffin later purchased a Judy Garland DVD at Wolfe’s register, and he laughed at this early memory. “I guess that was his signal.”

As a husband and a gay man from the South, Wolfe’s reflections on *Hide* echo the notion that Griffin’s story is more about relationships in general than gay relationships essentially. “It’s such an ordinary story of two people loving each other inside a home,” he said.

Falling in love in another millennium has afforded the real-life couple opportunities to reach the next level of “ordinary” that Hide’s Frank and Wendell could never achieve, but certainly not without a fight. In 2013, Griffin and Wolfe made two trips to the city clerk’s office in Morristown, Tennessee to apply for a marriage license, knowing they would be denied.

Their activist efforts for marriage equality were documented in a New York Times piece called “Struggling for Gay Equality in the South” and in a film made for the Campaign for Southern Equality. The two were finally married one the day of the Supreme Court’s historic decision last summer, their license issued by the same clerk who had denied them twice before.

“Even though [it’s 2016] and things are vastly different than they would have been then, I still felt like we hadn’t quite shaken off that atmosphere that’s portrayed in the book,” said Wolfe of their previous home in White Pine, Tennessee. Living together and getting married might have been their step toward normalizing their relationship “in a community that didn’t necessarily feel super welcoming of LGBT people,” as Griffin described it, but there is plenty of work to be done in the South.

Still, Griffin is less concerned with changing the minds of the homophobic as he is with making young people feel “normal” through his work.

“You always hope that maybe [the book] will fall, somehow by accident, into the hands of someone whose mind it will change,” he said. “But I want high school students to see that it’s possible to have a happy life and fall in love.”

SHORT REVIEW

The longstanding partnership of main characters Wendell Wilson and Frank Clifton—two elderly men who have kept their relationship secret from the North Carolina milltown where they have lived for many years since meeting in the 1950s—is unique by any measure. Living in isolation, the two are able to occupy a domestic space together in a way that would have otherwise been downright dangerous, especially in that era but still today. But the real meat of Hide deals primarily with the effects of isolation, the pain of aging, the burden of caretaking, and regret. Its themes are complicated by but not contingent upon the fact that Wendell and Frank are both men.

Griffin’s impressive debut is certainly a fine entry in the growing canon of LGBT+ fiction and is a prime candidate for a Lambda Literary Award, but Hide shouldn’t be pigeonholed too quickly either. Its absorbing depiction of truly universal struggles at the end of life is one that will resonate with any reader.