By Terri Schlichenmeyer, March 2018 Issue.

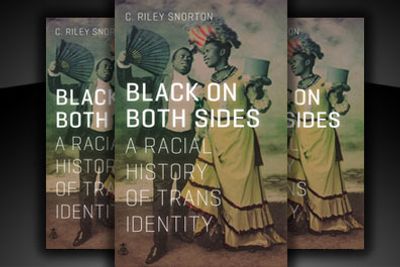

You look sharp today. This morning, you dressed with determination, putting confidence on your body in order to put it in your mind. You chose your outfit deliberately but, as in the new book Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity by C. Riley Snorton, there may be reason for a different direction.

When the Cornell University Library recently assembled a display of “queer and trans performance” items, there was a singular piece of paper that caught Snorton’s eye: it was a French postcard depicting two black “transvestite” performers, possibly in a minstrel show or at a cakewalk, which was likewise a popular form of entertainment, circa 1900. The library called it a “rare” piece, but Snorton shows that African American history is rife with examples of transgender identities.

During the Civil War, for example, archives indicate that many slaves, particularly women, dressed in men’s clothing in order to be seen as male and to avoid bondage. Even Harriet Tubman disguised herself as a man to deter arrest. Ellen and William Craft took it a bit further when Ellen dressed as a man, and her husband as her manservant, in order for both to escape slavery.

Black sex trade workers sometimes dressed as women, often to great mocking and even greater scandal. One was nicknamed “The Man-Monster,” a frightening 1836 moniker for Peter Sewally, also known as Mary Jones. Nearly a century later, Lucy Hicks Anderson, a madam, became “the first transgendered black to be legally tried and convicted … for impersonating a woman,” and was sent to prison for it.

And while some wish to keep their cross-dressing in private, others don’t mind becoming famous: Snorton cites national media sources for bringing forward the stories of Ava Betty Brown and Annie Lee Grant, both featured in Ebony and Jet magazines, the latter photographed in clothing for men and for women.

Black on Both Sides falters right from its very subchapter: large parts of the book are about people who temporarily dressed in clothing associated with those of another gender in order to escape situations, not because they were transgender. Here, it’s also about a white man who performed gynecological operations on enslaved women without anesthesia; they, and a Black cisgender friend of trans murder victim Brandon Teena’s, are included with the thinnest of connections.

Even comprehending this book is a challenge: single sentences, which are written in language that may test the most scholarly of readers, can often be measured in inches on a page; readers might also quibble with issues of definition, particularly “transgender” versus “cross-dressing.” Snorton refers to both in this book, but doesn’t seem to make very strong distinctions between the two.

To the good, the research done here is stellar. There’s a wide variety of case studies and interesting stories in this book – much more than readers might expect there’d be – but whether they’re accessible is quite another matter. Overall, Black on Both Sides offers an educational look back, but is a tough read missing some important distinctions.