By Terri Schlichenmeyer, July 2020 Issue.

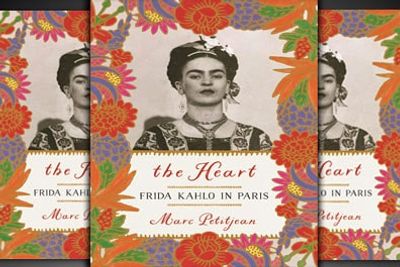

The Heart: Frida Kahlo in Paris by Marc Petitjean, translated by Adriana Hunter c.2020, Other Press

$25.00 / $34.00 Canada | 208 pages

Every brush stroke must have had meaning.

Every color, every shading, every wipe and fingerprint and trowel mark left by the artist became a portrait of metaphor and mystery: what was the artist trying to say? Was it just a painting or, as in The Heart by Marc Petitjean, was there a story behind it for observers to unravel?

Because his father had led a colorful life, Marc Petitjean was surrounded by artwork and objets d’art for most of his childhood. One of those works was a painting that Petitjean understood was important to his father. Later, long after the elder man died, Petitjean learned how important the painting was when a stranger inquired about his father, and the affair he had with Frida Kahlo.

Michel Petitjean was just 29 when he met Kahlo; she was 33, and was staying in France at the time, having gone there because André Breton, who’d founded the surrealist movement, had decided on his own that Kahlo was a surrealist painter. Breton told her that he wanted to do an exhibit of her work but when Kahlo arrived in France, she was angered that Breton was unprepared for both her arrival and her show.

She’d met Breton when he and his wife, Jacqueline, came to Mexico to talk with Leon Trotsky, who was living temporarily with Kahlo and her husband, Diego Rivera. The Bretons stayed the Rivera’s for several months — long enough for Kahlo to have a brief but playful sexual affair with Jacqueline before the Bretons returned to France.

Petitjean says that there is no way to know exactly how his father met Kahlo, but the first time they slept together “was the day Barcelona fell.” They didn’t speak the same language but he comforted her as best he could, and she grew to mean a lot to him. Later, he helped her pack up her paintings to return them to Mexico, and she gave him option of choosing any painting he wanted.

He chose The Heart.

In a surprisingly charming mixture of fact and fiction, author Marc Petitjean spins a dreamy tale of an artist and a painting that is in itself a mystery. That, the multiple hypotheses, and a lingering unknown make The Heart a captivating tale.

Petitjean depicts Paris in the pre-War years in a way that lets readers feel the devil-may-care extravagance of the city’s residents living in the shadow of Nazism and looming trouble, giving this book a dark sense of foreboding. He then imagines Kahlo’s political leanings and adds to her mystique, giving her a certain cheeky flamboyance and, with passages that seem as if they’re viewed through sheer white curtains, he shows us a Kahlo that falls easily in lust and love, but with a blithe sense of detachment.

Petitjean hints that his father was more upset about that than was Kahlo, but again — we’ll never know for sure. Still, readers that love art, biographies, historical mysteries, and Kahlo in particular will find The Heart to be a stroke of enjoyment.

c.2020, Brilliance Audio $25.99 | 4 discs, 4:53 listening time

c.2020, Sourcebooks $15.99 | 304 pages

You’ve always taken care of those you love.

You’ve ensured that everyone is safe and happily occupied. Elders have groceries, errands are done, and you keep in touch with the people you miss. You’re taking good care of everyone around you — but as in the new book The Extremely Busy Woman’s Guide to Self-Care by Suzanne Falter, who’s taking care of you?

In the last three months, if you’ve learned one important thing, it’s this: when it comes to doing for others, you are not a bottomless well. You give and give and give but lately, you find yourself running empty.

Something similar happened to Falter: after her daughter, Teal, died, she began to feel that nothing had meaning anymore and that the life she’d “cobbled together” wasn’t what she wanted. She’d left her husband and come out as a lesbian, but that was all she’d done for herself. She ran out of energy for everyone else and everything.

Desperate for something better, she quit working (which, she admits, isn’t an option for everybody). She started listening harder to herself and to others. She started asking herself what she wanted out of each new day she’d been given.

And from that sprang an awesome life.

If you’re depleted, she says, there are “essentials” you’ll need to heal, starting with plenty of sleep, exercise, and avoidance of food, drink, or substances that aren’t good for you. Be open to love but make yourself a priority. Learn to lean on friends and family; in fact, find an “action buddy” to help you get through. Take real time off — not just a turn-off-the-phone-for-the-evening time, but real vacations away. Learn to meditate or, at the very least, to sit quietly with yourself. Look for fun now and then and use it to “feed your brain.” Finally, once you’ve found the “essentials” that seem to work best for you, learn to implement them into your daily life.

“Get help where needed,” Falter says, “for that may make all the difference.”

Page through The Extremely Busy Woman’s Guide to Self-Care, and you may notice that this book is very new-agey. Very new-age-y, as in: “New-Age-y” should be on the cover in 4-feet-tall neon letters. You might also notice that if you’re an “extremely busy woman,” this book will make life even busier.

Filled with worksheets and demands to “breathe,” there’s a lot to do here to get this books’ full use. That doesn’t make it unhelpful: for anyone at the end of her corona-rope without a knot, it may be a complacency-squasher. Author Suzanne Falter writes with the voice of authority when discussing how she clawed her way back from the brink, using loss as a springboard for many of her best points — but beware: some of those points are from “Teal’s Journal,” making it even more new-age-y.

Still, for the reader who desperately needs quick bites of help in a hand-holding, alternative, worksheet-loaded format, The Extremely Busy Woman’s Guide to Self-Care may be the ticket. If that’s advice you truly need, take it.

c.2020, University of Iowa Press

$19.95 / higher in Canada | 328 pages

You spent days examining your life.

Sins: that’s what you were looking for How had you displeased God? How many lies, covets, dishonors? What have you done since — oh, when was your last confession, anyhow? They say the sacrament is good for your soul, and in Confessions of a Gay Priest by Tom Rastrelli, there’s a lot to tell.

Though he’d always known that he liked boys, little Tommy Rastrelli pretended the opposite when he was in grade school because marriage was what good Catholics did. His family was devout and Rastrelli never questioned God’s love. Not even after, he says, he was repeatedly molested by a doctor in his Iowa hometown.

For several reasons, he never told his parents about the abuse, enduring it for years until he’d convinced them that he was too old for a pediatrician. That God hadn’t saved him from a predator made Rastrelli slowly lose his faith and his self-respect. He stopped attending Mass and began questioning the Church’s teachings.

But then God called a shocked Tom Rastrelli to the priesthood.

It happened while he was at college, and the whole idea quickly consumed him. Gone was the plan to major in theatre; instead, Rastrelli began to explore a world steeped in mystery and ritual but overlaid with fear. Always believing that testimony against the doctor could save others from the same abuse, Rastrelli took legal action, knowing that scandal could ruin his chance to attend seminary.

There were many things undiscussable, in fact, and the court case was only half of it. As he progressed in his journey to ordination, the secrets included priestly kisses, caresses, and soft lies that a “backrub” was just a backrub. At nearly every gathering, Rastrelli was approached for sex or touched inappropriately, led to believe that celibacy had wiggle-room, plied with alcohol or favors, and left to deal with it alone.

He fell in misguided love.

And then he fell into a deep depression, with only one real way out.

The Confessions of a Gay Priest is a hard, hard book to read — it’ll make you squirm, it’ll make your eyebrows raise, you’ll want to toss it on the street and let semis run it over and yet, it’s stay-up-all-night compelling.

Beginning with his ordination (so you know-don’t-know the end of the story), author Tom Rastrelli tells a tale that will further shock Catholics already reeling from church-related scandals. This book, however, is not written in the same manner as is a diocesan document: Rastrelli is sometimes extremely graphic, both in the bedroom and in his various emotional states. He doesn’t pull back the curtains on his experiences, he rips them down and burns them. He used pseudonyms but tells details before softening his harshness with beautiful language, strong faith, and poetic distractions that play with a reader’s sympathy.

You can’t beat a book like that, though its graphic nature needs to again be underscored. For a reader who can endure a panoply of squirms, Confessions of a Gay Priest is worth deep examination.