By Laura Latzko, December 2016 Issue.

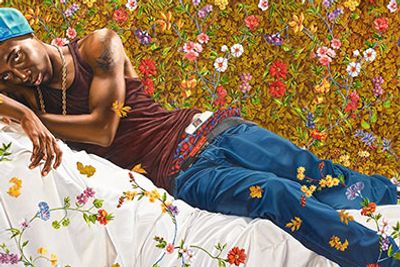

In bringing African American men and women into paintings resembling traditional European portraits, artist Kehinde Wiley makes powerful statements about race, class and gender.

The Phoenix Art Museum will display stained glass pieces, paintings and sculptures from Wiley’s traveling “A New Republic” exhibit in the Marley Gallery through Jan. 8.

According to Gilbert Vicario, Selig Family chief curator, the exhibit provides a glimpse into the evolution of Wiley’s work over the course of a 15-year period, beginning in 2001.

Wiley, who grew up in South Central Los Angeles, attended the San Francisco Art Institute and went on to graduated from Yale University.

In his first series of portraits, which he did in the early 2000s during an artist residency with the Studio Museum in Harlem, he set out to photograph and recast assertive and self-empowered young men from the neighborhood in the style and manner of traditional history painting.

Since then he has also painted rap and sports stars, but for the most part his attention has focused on ordinary men of color in their everyday clothes.

Wiley’s work has been featured in museums around the world and on the hit TV show “Empire.” In 2015, he received the U.S. State Department Medal of Arts.

The Power of Portraiture

In his paintings, Wiley often depicts African American men in modern-day clothing in poses similar to old masters from the 17th through 19th centuries, such as Peter Paul Rubens, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, Sir Joshua Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough, Edouard Manet and Jacques-Louis David.

“You have somebody who is dressed in streetwear, very contemporary clothing, but presented in this incredibly traditional and rarified way,” Vicario told Echo during a phone interview.

Through history, Vicario explained, patrons from European churches and courts have commissioned portraits to show off their wealth and power.

“In Western art history, the people that were always represented were either very high-ranking political figures or somehow related to church. For the most part, the peasants or the common people, these things weren’t even available for them to see, aside from the religious icons or the stained glass windows,” Vicario said.

“They were very much excluded from that tradition and that history.”

Wiley’s portraits draw attention to the lack of black subjects in art as well as conventions inherent in traditional European artwork.

“The fact that he uses everyday people in that context creates that friction between what we know about European portraiture and its connotations of class and privilege,” Vicario said. “That’s why these [paintings] have gotten some much attention and why they are so engaging.”

Addressing Diversity

When Wiley took an interest in art as a child, he noticed a lack of diversity in museums and art galleries. As he got older, he set out to change that.

“I fell in love with painting at a very early age, and I knew there were referees keeping the gates safe,” Wiley said during a press preview of the exhibit. “All of these wonderful pictures that I saw when I was 10 and 11 years old, powered through gentry, lapdogs and pearls, were part of the official narrative. You want to see yourself in them, and I think that’s what we have here. We have a type of art that says yes to standards of conceptualism but also yes to inclusiveness, yes to people who happen to look like me being on the walls.”

Although his work isn’t politically motivated, Wiley said it often draws attention to larger political issues.

“You can’t paint a bowl of fruit without being political. You’re black man painting said bowl of fruit. You’re a queer painting a bowl of fruit,” Wiley said. “There’s a rubric through which we view everything. I know that exists there. I know that’s part of the story, so I don’t have to break my back to try to politicize a moment.”

Rather than fight this, Wiley said he harnesses it for inspiration.

“What I try to do is keep eyes on that white glowing state of grace that got me into this game from the beginning, which is the curiosity about the world, the curiosity about mixing paint and making things happen, about confronting things that scare the shit out of me,” Wiley said. “As opposed to running away from it, I’m that kind of guy that really wants to run towards it and create something that has some sort of social or artistic merit.”

A Woman’s World

In his An Economy of Grace series, the artist represented black women in custom-made Givenchy gowns, in regal poses similar to high-society women.

“You’ll notice these long, flowy gowns, but they have these kind of wide, leather belts that distinguish them. It brings it more into a contemporary context,” Vicario said, adding that the visual aesthetics of the series makes it appealing to people from different backgrounds.

“It’s so cinematic. It’s so incredibly beautiful, and it really sticks with you,” Vicario said.

Wiley uses a process called “street casting,” in which he invites strangers to sit for portraits. As part of this process, subjects a painting from a book and reenacts the pose of the painting’s figure. By inviting the subjects to select a work of art, Wiley gives them a measure of control over the way they’re portrayed.

Approaching female subjects on the street, Wiley said, poses a different set of challenges than approaching male subjects.

“There’s a different dynamic. I might be queer, but there’s a male/female sexualized thing that happens in the street when you are asking someone to engage,” Wiley said. “It’s been an interesting project for me because it sort of lays bare foundation rules that have nothing to do with you. It’s not about the you that you occupy. It’s the world that you inherit.”

An International Palette

With his series The World Stage, Wiley expanded his dialogue by working with subjects in such countries as China, Israel, Jamaica, Haiti and Brazil.

“Up until then, he was only focused on African-American men and women. He began to think about representation on a global scale and in a global context,” Vicario explained. “Those are really wonderful because they broaden the conversation about multiculturalism in a nice way.”

For his international series, Wiley drew from different artistic styles and cultural traditions from around the world. This is especially evident in the colorful geometric and floral patterns used in the backgrounds of his paintings.

Wiley said while working with subjects in China, who appear in the same poses as Chinese socialist paintings, it was difficult to get them to smile.

“I decided to have them smile for an hour,” Wiley said. “They are being asked to hold that smile. It’s like this prison of the body, the desire to please perhaps. It starts with a Maoist notion of Cultural Revolution but then it starts to fold back into American notions of identity and the performance of docility.”

“A New Republic”

Through Jan. 8

Phoenix Art Museum’s Marley Gallery

1625 N. Central Ave., Phoenix

602-257-1880